![]() >> Artworks by Sen + Sonja Interactive work Sonja's c.v. Made in 2002 Arranged by Medium A tour via thumbnail images

>> Artworks by Sen + Sonja Interactive work Sonja's c.v. Made in 2002 Arranged by Medium A tour via thumbnail images

The Exchange - Colonising Oxford (1 - 19th October 2002)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Colonising Oxford - Change is a Law of Nature | Colonising Oxford with snails |

Colonising Oxford -The Exchange Table |

Colonising Oxford by boat | Olonising

Oxford - Readings | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| October 4th | October 8th. |

October 4th, 5th, 7th, 17th. |

October 18th | October 19th | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

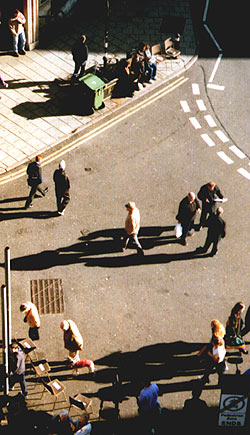

Oxford city centre  The arrow on the left indicates the location in the Cornmarket where I did two performances ("Colonising Oxford -Change is a Law of Nature" and "Colonising Oxford by boat") and where I placed the table ("The Exchange Table"). The arrow on the lower right is where "Colonising Oxford by drawing" took place. "Olonising Oxford - Readings" took place on the four corners of Carfax. |

|

This performance required local artists to respond to black and

white pictures from a foreign place, to draw images of another

country -- as they pictured it -- |

On one level this was intended to be fun for them and for those passing by.

Some silliness on the streets, yet, there was a sting in the tail - like the issue of colonising in general - to some degree we are all colonisers and colonised. Colonisation is always a two-way process.

I am not saying that colonisation is a good or bad thing or that it is innocent either.

In fact no colonisation is benevolent.

The difference between exchange and colonisation is that the coloniser has the upper hand.

I came to thinking about these issues when applying for this artist-exchange.

Since I was going to Oxford on an inter-city exchange, I wanted to

relate my work to the 'exchange' theme.

An exchange takes place in

the context of an encounter with another person, which led me to

think about what happens when one person encounters the other,

and in particular meets other cultures.

The Dutch and the English, both

colonising nations, have affected other cultures, and have been

affected in turn as the colonised peoples flowed back to the

"mother" country. Colonisation has been not all bad, and the influences have not all been in

one direction. What is more English than tea, more Dutch than

coffee?

And this didn't start or end with the colonial

age: England after all has been colonised by the Normans, Angles,

Romans, Vikings, fast food chains and western jeans -- and now by

6 Dutch artists.

So, for these reasons "Colonising Oxford" seemed a fitting title for my performances in the context of this exchange.

For my final performance, I was not allowed to use this title by the Oxford city council twinning officer, May Wylie.

While the artists (and my definition was anyone who considered themself an artist) were at work, my role was to supply their materials and make sure no one disrupted their work, and to keep the peace. So at times I reassured policemen and at other times answered questions.

The artists arrived in small groups of twos and threes during the two-hour stint and generally made one or two drawings.

Some (see the images below) improvised more than others. As this artist walked around the other drawings marking out her footsteps, another followed with texts commenting on the movement of the footsteps. At another point, two artists jumped around the squares of another drawing.

|

Later another artist, who was also the coordinator of this artist exchange, insisted that I must remove what she considered inappropriate responses on the footpath. These were the footsteps and texts. In fact she insisted, telling me that she was the one who had obtained council permission for the drawings.

I felt uncomfortable about this: I did not want to censor the responses of the colonials, and besides, as the coloniser, I did not want to get my hands dirty. I did not want to judge the effects of my colonising: that would have gone against what I wanted the piece to be about, and she was insisting that I do this. |  One of the 'colonised' artists mops away some footsteps and words drawn by the other Oxford artists.

One of the 'colonised' artists mops away some footsteps and words drawn by the other Oxford artists.

|

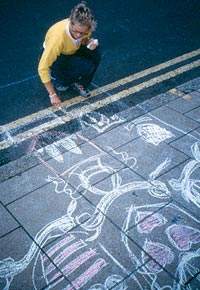

Colonising Oxford by drawing.

Colonising Oxford by drawing. This incident set me thinking about my role in these performances and what I was aiming for. The concept in "Colonising Oxford by drawing" was the role of images of the 'mother land.' The particular drawings or words did not matter. So it felt contrary to the concept of this work for me to have a hand in making editorial decisions about the responses of the 'natives.' |

In my script, she should have remained one of the colonised, who could be selective about what was 'right' in her Oxford.

But she thought she should tell me what to remove -- she was trying to write the script of the performance by influencing my behaviour as 'coloniser'. Her argument was that because she had organised this exchange, she had to control the content, so that future twin-city artist exchanges would not be jeopodized. I did not know how to respond. Then she brought a mop and took over the editing herself. I was relieved. I could resume my status as a benevolent coloniser.  |

Colonisation does not happen at the moment of conquest, in the sudden clash of peoples, but in the gradual and mainly everyday adaption that follows. I wanted my works to mimic the gradual adaption and adoption of a new source, in activities that are ordinary and accessible:

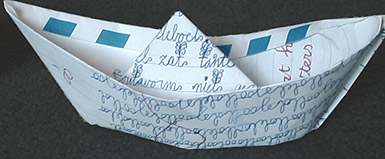

drawing, touching artifacts, making paper boats, reading. drawing, touching artifacts, making paper boats, reading. Give and take was also part of the process. |

Colonising Oxford by drawing.

Colonising Oxford by drawing.

|

| I wouldn't have been a successful coloniser, if I had allowed no room for my own adaption to the responses of the colonised. I wasn't importing finished works of art to lay them out on the streets of Oxford.

As you see, on the left, some drawings extended onto the street. While I was there, the buses drove around these. And others parked their bicycles. |

|

|

|

|

|

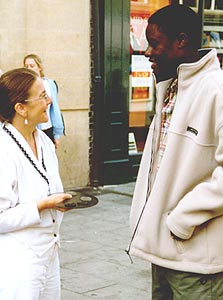

Sonja van Kerkhoff in white conducting the Change is a Law of Nature performance in the Cornmarket, Oxford, 4th October, 2002. Photographs: Hilary Kneale, U.K.

| |

|

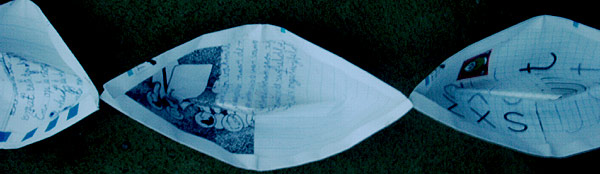

Next day, I presented myself as a Dutch artist with art currency to trade. Each translucent coin bore the text "Change is a Law of Nature". My job was to convince them of the worth of this currency. Although it appeared that I was encouraging them to buy or trade with me, we often ended up discussing the issue of 'value' or 'values'. What they really were valuing was the trust they developed in me, the artist, and through that in the art object.

The coins are transluscent 'small-change', as tokens of the exchanges taking place in the immaterial economy when people really communicate. |

|

Sonja van Kerkhoff, in white, conducting the Change is a Law of Nature performance in the Cornmarket, Oxford, 4th October, 2002. Photographs: Hilary Kneale, U.K.

This was the missionary part of the colonial endeavour. People taken at random are persuaded to take part in a piece of performance art by engaging with me in a conversation about values.  I first developed this performance in 1996 for a time-based arts festival in Hull, and have performed it in a few places since.

I first developed this performance in 1996 for a time-based arts festival in Hull, and have performed it in a few places since.

To more about the "Change is a Law of Nature" performances. |

|

|

My previous performance of this piece was during the 2001 Christmas shopping frenzy in Santa Monica, Los Angeles. That was hard work. In Oxford it was a breeze, people were very open and willing to chat. In fact, Oxford felt very relaxed in this way, more like a village than a city.

|  Sonja van Kerkhoff, in white, conducting the Change is a Law of Nature performance in the Cornmarket, Oxford, 4th October, 2002. Photograph: Hilary Kneale, U.K.

Sonja van Kerkhoff, in white, conducting the Change is a Law of Nature performance in the Cornmarket, Oxford, 4th October, 2002. Photograph: Hilary Kneale, U.K. |

On October 8th, I led 9 snails out from the front door of the Ashmolean Museum. |  |

The spiralling texts on them in Dutch or English, with a dash of Maori, allude to changing times and perspectives, in nature, culture, and the arts. The materiality of the snails contrasted with the enormous facade. Taking them down the steps symbollised taking them into the citizen zone.  |

|

These were the smaller snails from the "Dans le jardin des beaux arts" installation which have been exhibited in a number of locations. See: Their first airing As it happened, some texts were from Oxford author, Lewis Carroll's "Alice in Wonderland", although I chose the texts because they related to the relativity of art, nature and culture. The texts were: In the garden of Fine Arts. "Well, I'll eat it," thought Alice, "either way I'll get into the garden." Kunst is cultuur ineengestrengeld met de natuur, hoe vaak zij ook ontward lijkt te zijn. |

|

|

(translation: Art is culture intertwined with nature, however many times removed)

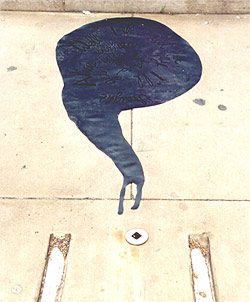

Holding my breath to hang onto time - te wahi o nga hau iti. (translation: - the time, place, season of small/short breaths) "If it makes me smaller I can creep under the door." "Daag jij mij uit!" lachte de haas. (translation: "You challenge me!", the hare laughed.) Portrait of the artist as a small black hole. "If it makes me larger I can reach the key." de toekomst beidt de beste perspectief. (translation: the future has the best odds) |

|

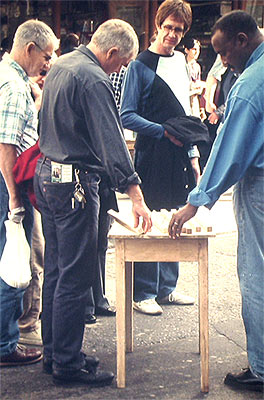

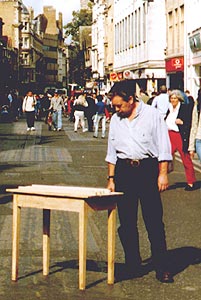

I left artifacts on a table in the middle of a pedestrian street during the lunch hour.

When I orginally made the engraved sticks ("Certain Measures") in 1993, I built a large wooden bar-height table. The sticks were scattered on the table (a table, not a desk or bench, because a table related more to the idea of everyday consumption). The public could handle, read and mediate or debate about the sticks and the texts on them. In 1999, when I exhibited the work in London, I didn't want to transport the table so the curator supplied me with one.  |  Most of the texts were my own thoughts concerning the spiritual within the material, with some quotations from the "Hidden Words" by Bahá'u'lláh.

Most of the texts were my own thoughts concerning the spiritual within the material, with some quotations from the "Hidden Words" by Bahá'u'lláh.

It was a low round table and he made a pedestal for me to put it on. It ended up being too high for some, so I put a stool next to it. Some people climbed up to look down, others reached up The table as an object now played a greater role in the exchange with these sticks and texts. I decided then that finding a new table for each new location suited the idea of the sticks being 'tools for meditations on exchange'. The work becomes a mix of what I have brought (imported) and what is available locally. See other locations of this work. |

| This old school table was just perfect for the Oxford Cornmarket. It was small so it was not intimidating, and low so the objects could easily be seen from a distance. I would put the table out for a few hours and then sit or stand nearby just watching people, taking time out to observe the locals and their interactions with my artifacts. |

Because the table was on a street rather than in a gallery, the focus of the work changed this time, from the texts to the flow of people around the table of artifacts. Reading and touching became only part of the interaction. |

|

|

A woman glances as she walks by, the man changes direction, only seeming to notice the table out of the corner of his eye. Each person made some series of quick decisions: to turn aside, to look in passing, to stop and turn a stick over to read the whole text; to be interested in the work, to be annoyed at those standing still. It was fascinating to watch how the table affected the pedestrian flow. It was like watching a series of frames, each defined by several people's interactions. |  |

| Leiden and Oxford are museum cities, each with an ethnographic museum (in Leiden, the National Museum for Ethnography and in Oxford, the Pitt Rivers Museum) containing an eccletic collection of artifacts. In the Pitt Rivers Museum in particular, items from all over the world were crammed together without much in the way of context. Coming from New Zealand myself, I found it strange to see intricate Maori weaving and carving stacked in glass cases with objects from other cultures. This set me thinking about the history of collecting as part of the colonial past. |

Generally I just watched, holding a book so it wasn't obvious that I was watching, and because it seemed right just to be there but not to do anything. So even when the police car or ambulance came by, I waited to see what would happen. Each time, a member of the public responded by moving the table out of the way. | People still spent time touching and reading, and some sought me out with questions or remarks.

|

A member of the public carefully picked up the table to move it to the side, when a vehicle drove past. |

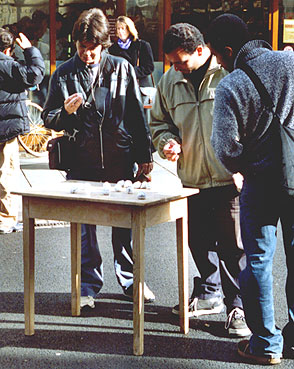

On Oct 4th, 5th and 7th I laid eight sticks on the table. This was my "Certain Measures" work, with five sticks bearing texts in Dutch and three in English. To more about "Certain Measures". On October 17th I laid about twelve small white balls on the table along with a sign "Pick up a seed and finish my sentence." People picked them up, rattled them (they made a soft sound when rattled) and read them to themselves or to each other. |

The Exchange Table, Cornmarket, Oxford, 17th October, 2002. |

|

|

The Exchange Table, Cornmarket, Oxford, 17th October, 2002. Each hand-made plaster 'seed' rattled and bore an incomplete sentence on issues related to world peace and cultural diversity. |

The Exchange Table, Cornmarket, Oxford, 17th October, 2002. |

The Exchange Table, Cornmarket, Oxford, 17th October, 2002. |

Some examples of the texts were: "We can choose responses that are" "We should care about ourselves and our visions. My vision is" "War is culture, not nature because" "Take a fresh look at the 'enemy' without (the letters are illegible around a point in the form)" These texts wound round and round the balls so you had to turn them to read, and so that the final word met the beginning or met another word in the sentence. I did this not just to make it playful but also to suggest that any following word, like making a choice, meant choosing a particular course. |

|

These 'seeds' are from another performance, "The Living Creature" created for a London city park in 1999. There the subject matter was influenced by the other artists' works in the same location. I wanted people to follow my train of thought and then to finish it for me, on a piece of paper. In the context of Colonising Oxford, I brought these thoughts and gave the locals the freedom to finish my sentences for themselves (I don't ask them to write them down this time). Was I directing their thoughts, or offering an option or opportunity? Two days earlier, one quarter of the content of my "Readings" performance had been censored. I had been directed, told what I could say in public, and it left a bad taste in my mouth. I didn't know what to do. |

|

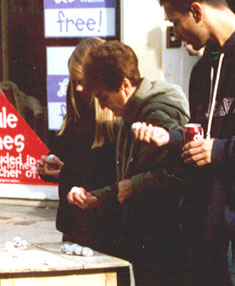

Cornmarket, October 18th, 2002. |

A video clip will be added oneday (3 min + 50 sec, 200 x 160 pixels, 28 mb) |

Boats and language were the vehicles of colonisation, when the Dutch were vying with the English in the 17th century. The English won both races: they had deeper harbours. Fortunately my boats needed no water!

One passerby told me that Oxford was the city furtherest from the coast in England.

Video stills: Clare Carswell.  Photograph: Clare Carswell, U.K. Photograph: Clare Carswell, U.K. Video Stills: Clare Carswell, U.K. Video Stills: Clare Carswell, U.K.

|

Photograph: Clare Carswell, U.K.

Photograph: Clare Carswell, U.K. |

Text adapted from Cornelius Vroom: Marine and Landscape Artist, by George Keyes, 1975, p. 17 |

|

|

|

A passerby commented that the tarseal I was working on was

only a few days old, and so only just ready for my 'colonising'.

|

|

|

|

|

By the creature that washed towards me. Yet another ship passed, familiar sails stretched Upon racks of wind, ropes taut against spars, Enough to rip a man's hand trapped there, Careless with rum, wistful for a shore Of women. None of these things disturbed me Then, not the commandments of braided Officers, nor the sobbing of offenders Tied naked to the mast, cold winds like gannets Gathering at their flesh. For years I had known These scenes, and I had fogotten the years - Until it broke the waters, close To my face, salt splash burning my eyes Awake. One section from the ten verse poem "Turner" by David Dabydeen, 1994. Dadydeen wrote that in 1840 J.M.W. Turner exhibited the painting, "Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying" (commonly known as the "Slave Ship") and that Ruskin thought that 'Slave Ship' represented 'the noblest sea that Turner ever painted...'. Ruskin wrote a detailed account of the composition of the painting, dwelling on the genius with which Turner illuminated sea and sky in an intense and lurid splendour of colours. Its subject, the shackling and drowning of Africans was relegated to a footnote in Ruskin's essay. Dabydeen's poem focuses on the submerged head of the African in the foreground of Turner's painting. It had been drowned in Turner's sea for centuries. When it awakens it can only partially recall the sources of its life. |

"...each moment...

Is but a quiet watershed, Whence, equally, the seas of life and death are fed" The Amazon and Orinoco basins are linked by the Casiquiare Canal, from whose highest point, if it could be detected, water presumably flows in two directions. The geography of change begins where change is barely visible, a zone of shadow at the edge of night. Between the shallow catchments of the Amazon and Orinoco the Casiquiare's natural canal trembles on a watershed where any breath in the breathless spongy jungle could start the balance. A hair-line in the black water from which the current slips away; one particular period in which the great Casiquiare begins to slide over the watershed and down to its several waiting mouths, like the python that lies digesting motionless its meal until, at a certain critical level of repletion, the eyelids rise and the great coils begin to flow, beautifully, to a certain end. Some kind of change has occurred: one hair, laid on the water, begins to drift and the watcher thinks of the sea. Humbolt and Bonplaud continued their journey on the river by canoe as far as the Orinoco. Following its course and that of the Casiquiare River they proved that the Casiquiare River formed a connection between the vast river systems of the Amazon and the Orinoco. For three months Humbolt and Bonplaud moved throught dense tropical forests tormented by clouds of mosquitos and stifled by the humid heat. Their provisions were soon destroyed by insects and rain; the lack of food finally drove them to subsist on ground-up wild Cacao beans and river water. Yet both travellers, buoyed up by the new and overwhelming impressions, remained in the best of spirits. (Encyclopaedia Brittanica.)

|

Photograph: Clare Carswell, U.K.

Photograph: Clare Carswell, U.K.

| Behind me is the Carfax intersection, the heart of Oxford, which was the location for the performance which was censored by the Oxford city council. |

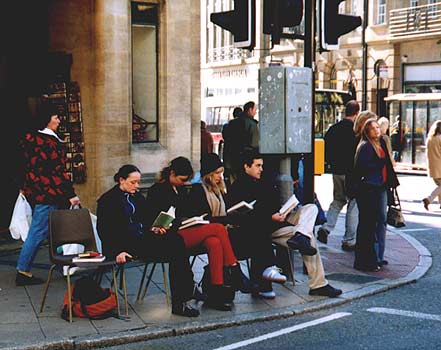

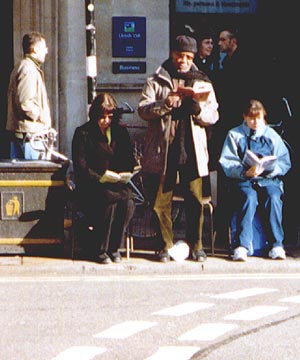

Fore to background: The "Poets" group with the the "Narrators" group on the opposite side,

Fore to background: The "Poets" group with the the "Narrators" group on the opposite side, while the traffic light was on red. This performance was to consist of four groups of Oxford volunteers seated in chairs on each corner of the Carfax intersection, one group engaged in silent reading, another in reading poetry, the third reading prose, and the fourth debating amongst themselves some questions relating to language and colonisation. The authors used for the first three groups were from countries with an English colonial past: Ben Okri, Toni Morrison, John Agard, Janet Frame, David Dabydeen, Margaret Atwood, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Catherine Obianuju Acholonu and others. Their works were all found in Oxford bookshops, homes and the public library. |

| The readers and the debators were to remain seated and continue with their activities for the whole hour, while each individual in the two other groups would stand and read in turn. When the traffic lights turned red, a "Poet" and a "Narrator" reader (on opposite sides of the intersection), stood reading aloud. They stopped after about a minute when the traffic light changed to green. |

The Reader's group on the corner of St Aldate's and High Street

The Reader's group on the corner of St Aldate's and High Street |

The "Narrators" while the traffic is on red.

The "Narrators" while the traffic is on red.

|

So these poems and stories were heard in snatches, in intervals in time with the

flow of the pedestrians crossing the streets.

On the whole I could see that for all concerned it was an effective piece. In the poets' group, two readers were quite dramatic in their presentations. On the opposite corner, the narrators seemed to be involved in a meditative process. The silent readers were simply there, as if they had been reading in their living rooms, and the walls had vanished. The only obvious reaction from the public was that one person sat in an empty chair next to the narrators to eat his lunch. Many people stopped to read the texts on the empty chairs (which will be explained below). Some pedestrians stopped briefly behind the groups to listen or look over their shoulders. The readings were only audible close to the readers, so the activities on the other quadrants were seen, not heard. |

|

Carfax Intersection |

> >High Street > The Narrators <The Cornmarket > The empty chairs of the debators |

< The Readers > St Aldate's < The Poets |

|

This performance was marred by being censored by May Wylie, the twinning officer of the city council.

I was not allowed to use the title "Colonising Oxford", no publicity was allowed for this piece, all the reading material had to be submitted for her to approve and one group of participants, the debators, was not allowed.

So instead of my intended four groups at each corner of the Carfax (four-forked) intersection, there were only three groups. My response to the mutilation was to symbolise the "forbidden" group of debators with empty chairs, each bearing one of the questions which were not allowed to be discussed. If a painting is removed from an exhibition by the censor, it can be hung somewhere else, but a damaged performance cannot be restored, so the title, even in hindsight, can only be "Olonising Oxford". |

The "Narrators" group with the empty "Debators" chairs on the lower left. |

Looking over the shoulders of the "Readers" with the Carfax tower in the background and the "Poets" group to the left of this. Photo: K. Sentance, U.K.

Looking over the shoulders of the "Readers" with the Carfax tower in the background and the "Poets" group to the left of this. Photo: K. Sentance, U.K.

|

My intention was that people seated in these chairs would discuss these questions among themselves, not present the questions for the public to respond to. As on the three other corners, the public would be able to hear snipbits of what these volunteers were saying. They could not participate actively. The 'colonisation' was only to do with those seated in the chairs. Putting the questions on these chairs seemed better than having a complete amputation of the group, but it was not an adequate substitute. It should have been an auditory experience of people engaging with colonisation and language, whereas here the written questions were experienced as statements addressed to the public. Diana Bell, the coordinator of the exchange, and May Wylie wanted me to rename my work 'Other Voices'. They said that a debate on colonisation would cause race riots! That such work would threaten the non-political nature of twin city exchanges. |

The "Narrators" while the traffic is on red, with Ibrahim reading in Arabic from the Koran.

The "Narrators" while the traffic is on red, with Ibrahim reading in Arabic from the Koran.

The participants were welcome to choose their own material if their mother tongue was not English. |

It was clear that neither of them understood that this was performance art, not protest or a community arts project. But their judgements were backed by Maureen Christian, the Councillor responsible for Culture. The arts officer of the city council was not involved, and he was not able to have any influence once he did hear what was happening. Ironically, it was because of my proposal for this performance that I was accepted for the exchange. Diana Bell objected to particular poems or authors such as Salman Rushdie, and most strongly to having non-English speakers read in their native tongues. |

|

I was open to input, because I wanted the content of the piece to be found in Oxford itself. The questions for the debators and the texts to be used would come out of my exchanges with Oxford. I perceived Diana's criticisms as advice rather than as instruction, and I was happy to debate with her and let her influence me, as part of the give and take involved in the colonisation theme. But in the end, it was my art work and I was the coloniser. |

"The Poets" group. Photo: K. Sentance.

"The Poets" group. Photo: K. Sentance.

|

|

Then, while I was London, two days before it was scheduled, I heard from another artist that Diana had cancelled the performance without consulting me.

Among other things her email stated that she was unhappy with the link between colonisation and asylum seekers. The email continued to say that the poetry reading could go ahead, but that many of the readers did not want to read without any practice. So after rescheduling the performance for a week later, I thought I would have to convince a few of my volunteers that they would not have to provide a polished performance. The point of the performance was not that the authors should be presented in public readings, as in a theatre, but that the readers should give their responses to the colonised voice. |

The "Readers" on the corner of St Aldate's and High Street

The "Readers" on the corner of St Aldate's and High Street

|

|

Colonisation is more about process than form. However I found the volunteers hadn't been concerned about this to start with.

On October 15th I had a meeting with May Wylie and Diana Bell. May Wylie said that my work could in no way be political. I agreed: it wasn't.  I was using the word 'colonisation' as a medium, treating it aesthetically, relating

it to culture and language, and to processes today (as indicated by the colonial literatures in Oxford libraries) rather than just to historical 'guilts'.

I was using the word 'colonisation' as a medium, treating it aesthetically, relating

it to culture and language, and to processes today (as indicated by the colonial literatures in Oxford libraries) rather than just to historical 'guilts'.

It seemed from the meeting that the word colonisation was that-which-may-not-be-named.  It was claimed that the word "colonisation" was a negative reference to asylum seekers. It was claimed that the word "colonisation" was a negative reference to asylum seekers.

It was as if the world was in two parts, English and the 'other voices', which could all be summarised under the heading 'asylum seekers'. I was told that there was antagonism towards the nearby asylum-seekers' centre, but as a visitor I wouldn't understand this.  Councillor Maureen Christian was later quoted in the Oxford Mail of October 21st as saying that "We were concerned for her safety and we thought that this event might cause a breach of race relations. It would be like an Oxford artist going over to Holland and giving talks on how the Dutch were colonial. It has nothing to do with modern-day life." Since I had not met her, I do not know whether she was misinformed about the piece, or simply did not understand that this was an art piece, not a lecture from me.  During the meeting on October 15th, I proposed to do the work independently. But I was told that because I was in Oxford as part of the twin-city exchange, everything I did was automatically connected with the city council. It was at this meeting that I was told not to use the title "Colonising Oxford", not to publicise the work, to bring all the reading material to the twinning officer for her approval, and that I could not have the group of debators. In fact it would have been difficult for me to do the work independently in the time I was in Oxford, since Diana Bell was also my main channel of contact with Oxford artists, whom I needed as volunteers. Few of them would have been willing to go against her wishes. |

The books from bookshops and the public library,

on the desk of the Oxford city council twinning officer, for her to approve.

The books from bookshops and the public library,

on the desk of the Oxford city council twinning officer, for her to approve.

|

Here the Council twinning officer has dictated the content of an artwork by a visiting artist.

This is ironic for a city that hosts a famous debating club, The Oxford Union, and has a name for academic excellence. But that is "gown", and I was dealing with the "town". Democratic countries do have controls on speech in relation to libel and inciting hatred, but this is a legal responsibility after the act, not censorship in advance, and in other countries, this control is carried out by courts and not by council officers. Although I was happy with how the revised performance went, it was still marred by the censorship. I had fewer volunteers and emotionally I felt torn. I found myself fighting a battle. I didn't know whether to be silent about being censored or not: going to the press would mean that the political arguments could overshadow the poetical atmosphere of the piece. I also did not want to jeopodize any future artist exchanges. In the first instance, I am an artist and this is an art work. I didn't want to mis-use any publicity just because I'd been badly treated. |

A point made by one of them about the value of having artist exchanges of the amateur watercolourist level, helped me to realise that I would not be damaging the professionality of the arts in Oxford by going to the press. Any professional artists involved in an exchange in Oxford should be aware of the conditions prevailing. Had I known that the content of my work could be controlled by non-professionals, I would not have gone.  Ms Kerkhoff also had to have the literature to be read, passed for approval. ... She has been told by the city council that any discussion of colonialism is contentious. It is difficult to see, however, how the council will be able to prevent such a discussion, or to prevent Ms Kerkhoff making this part of a public art work exploring the metaphorical possibilities of 'colonisation' and its reverse (the phenomenon of strong literatures from colonised countries, known in the recent history of the Booker prize as 'the Empire strikes back'). She has, after all, not been employed by the Council, and her four small groups of silent readers, poetry readers, prose readers and debaters are not likely to obstruct the way, being seated strategically around the intersection... Ms Kerkhoff says that it is a pity that the row has shifted attention to the issue of censorship, whereas the performance was intended to be about openness to reciprocal influences from other cultures and literatures. Her texts, she points out, have all been found in the shops and libraries of Oxford: the "colonising" influences are already here - but not perhaps the openness. |

Front Page of the Oxford Mail, October 21st 2002

Front Page of the Oxford Mail, October 21st 2002

The article by Roseena Parveen is below. |

In response to the press release there was a radio interview on the evening before the performance between an Oxford artist and the twinning officer, during which it was claimed that this was not censorship but a question of traffic safety and that I had been offered another location.

On the Monday after the performance, the Oxford Mail carried a front-page article headed "Council bans Dutch artist: fears of unrest and vistor's safety". It was wildly innacurrate, claiming among other things that I was at odds with the other Leiden artists, that inter-city relations had been "tested", and that the Twinning Society had been involved in the controversy. None of this was true, but the Oxford Mail didn't to print my corrections in a letter to the editor (see 'Olonising Oxford' below): |

|

Sonja Kerkhoff was among six artists from Leiden in the Netherlands who were invited on an exchange visit to Oxford. But relations with the Dutch city were tested when a closer look at her work raised concern among city council officers who banned her performing at Carfax over the weekend. Ms Kerkhoff said she felt the ban had infringed her civil liberties and right to express herself. Colonisation The city council said her work, which focuses on England's history as a colonial power, could provoke public unrest. But it claimed that the main reason for banning the performance planned on Saturday was for Ms Kerkhoff's own saftey. The work, entitled Colonising Oxford - readings, involved groups of people being stationed around different parts of the Carfax traffic lights junction with Cornmarket Street, High Street and Queen Street. Each person would, when the lights turned red, read a piece of literature in English by an author from a former colony. Maureen Christian, a city councillor and member of the twinning society, said: "She wants to put people right at the traffic lights. People are already frightfully irate around there. It's a very busy corner." "We were concerned for her saftey and we thought this might cause a breach of race relations. It would be like an Oxford artist going over to Holland and giving talks on how the Dutch were colonial. It has nothing to do with modern-day life. "She has not been censored. It's just a silly place to do this. We have suggested alternative venues such as Gloucester Green but it was not good enough for her." Ms Kerkhoff said that speakers would have been positioned so as not to affect traffic in the area. She had considered going ahead with her performance despite the ban, but changed her mind at the last minute. She said: "This has been about concerns that my work might damage the name of the council. The whole piece was about local individuals looking at the issues of colonisation. I am not presenting it as something good or bad. It is not enticing antagonism, but brings back the (page 3) colonised voice to Oxford. I am a responsible person. I think the council was misinformed about the nature of the piece." Mrs Christian said the row would not sour relations between the twinned cities because the other artists agreed with the council. She said: "The artists from Leiden are not upset. In fact, they are on the side of the council. Ms Kerkhoff has gone round other people giving a one-sided view. Unfortunately, she seems to be at odds with the other Leiden artists." Leiden is one of five cities twinned with Oxford - the others are Bonn in Germany, Leon in Nicaragua, Grenoble is France, and Perm in Russia - and the twinning society works to develop relations between the communities. roseena.parveen@nqo.com |

Olonising Oxford

I would like to correct some mistakes in the Oxford Mail’s front-page article on Monday (‘Council bans Dutch artist’). First, the article says that the Council banned the performance and it did not take place - but it did take place. Councillor Maureen Christian’s concerns about the risks to safety and race relations arising from reading poetry and debating literature in public (!), were proved unfounded. However the work was performed in a censored form, since May Wylie, the Council’s twinning officer, ruled that I could not have the planned group of five debaters on the Cornmarket. Instead, I printed the questions which were not to be debated on paper, and put these on empty chairs. Second, the article claims that “relations with the Dutch city were tested,” but I have no evidence that anyone in the Netherlands even knew about the issue. Nor did I involve the other Dutch artists, who were in Oxford to make art works. It would not have been professional to drag them into this bit of political silliness. Third, the article says that alternative venues were offered to me. This is not true. However, May Wylie suggested that my work was something for Hyde Park. An excellent venue but it lacks -somewhat - the connection with Oxford. Fourth, the Twinning Society was not in any way involved. Their work in promoting twin city ties is very much appreciated. The decision was made by May Wylie, who also insisted on approving all the literature to be read. These were poems and prose by non-English authors such as Janet Frame, Ben Okri, Margaret Atwood, John Agard and Toni Morrison. The performance was about reciprocal influences from other cultures and literatures. I found my questions and texts in the streets, shops and libraries of Oxford. May Wylie also ruled that I was not to use the word ‘colonisation’ in the title of the performance. In deference to her, I have called it ‘Olonising Oxford.’ This affair is a storm in a teacup. It would however be advisable, in future twin-city exchanges, that questions relating to the artistic content should fall under the Council’s Arts Officer. Professional artists are not likely to come to Oxford in twin-city exchanges, if a condition of the exchange is that the twinning officer can censor the content of their work. The Friday version, The Oxford Times published two supportive letters on October 25th under the heading "City council must address question of censorship of artists." Jo Stannard wrote, "The performance was a thoughtful investigation into English as a global language, and took place in a symbolic location - the central crossroads of this University City. Whilst it may have baffled some members of the public, it was clearly not likely to provoke unrest or disrupt traffic as has subsequently been claimed... ...if they wanted control over the artistic content, then this should have been stated at the outset." |

"The Poets" group. |

Helen Ganly wrote,

"Veronica Quilligan, the distinguished Irish actor, read poetry by Paula Meehan and passages from James Joyce, and was very happy to take part in what proved to be a gentle and symbolic work, as anyone passing Carfax on Saturday morning would testify.

I feel that the use of the word colonisation with its sad connotations, is what produced the anxiety all round. The City Council has to be vigilant about activities which have the potential to arouse political or racial hatred , and it is right that it is so. I, myself had to answer some searching questions before projecting slides about 'homelessness' in Cornmarket street, some years ago. Perhaps, in the future, the arts development officer, who has been appointed by the city council, should be asked to conduct this kind of inquiry. He will be knowledgeable about contemporary art practice and has been appointed by the city council. He, or she, should be able to discuss the proposed project with the artist in a way which is not perceived as hostile or threatening. These important questions must be addressed now, so that the long and fruitful relationships with artists from other countries can continue. The questions about 'censorship' need to be addressed now for the benefit of everyone, including the artists, who live in the city of Oxford." |

The empty "debaters" chairs,

The empty "debaters" chairs,

each with a question placed them. My intention was that people seated in these chairs would discuss these questions among themselves, not present the questions for the public to respond to. |

Below are the questions I placed on the empty chairs during the performance.

Has Oxford been colonised? Language is a means of colonisation. Should Oxford consider having bilingual schools in some areas? How responsible are the Dutch for the history of apartheid? How responsible are the English? Should the Dutch and / or the English be contributing in restoring the South African economy or actively helping to restore native cultures because they were once coloniser? After England was colonised by the Normans, French was used as the high-status language in England for three centuries, and the Old English language of before the invasion vanished as a living language. When does the past cease to be "our loss" or "our victory" and become just the past? Debate the proposition: virtual colonisation via the world wide web will be more effective in reducing the number of different languages than actual colonisation was. |

As on the three other corners, the public would be able to hear snipbits of what these volunteers were saying. They could not participate actively.

As on the three other corners, the public would be able to hear snipbits of what these volunteers were saying. They could not participate actively.

The 'colonisation' was only to do with those seated in the chairs. Putting the questions on these chairs seemed better than having a complete amputation of the group, but it was not an adequate substitute. It should have been an auditory experience of people engaging with colonisation and language, whereas the written questions were experienced as statements addressed to the public. |

|

Postscript A day after the article appeared in the Oxford Mail, I received the following email from Councillor Craig Simmons. Myself and Oxford's other Green Party Councillors were saddened to hear of your treatment during your recent visit to our city. We DID NOT agree with the Council's decision to ban your work. If you wish to return and perform again in Oxford we are happy to support you. |