![]() Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6 Sonja's c.v. Sonja's Design page Sonja'a art made in 1998

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6 Sonja's c.v. Sonja's Design page Sonja'a art made in 1998

part seven nederlandse versie

Memorials (Gedenktekens),  |

My work often is concerned with art as experience, combining the conceptual with the physical. In Memorials, the viewer first encounters a plaque with the text of a story about a feminine spirit's encounter with a garden, which clothing behind as a sign of mercy (memory). |

Mycelium, 1995

Made for the group exhibition

Mycelium incorporating the 22 artists'

works, Landbouwbelang, Maastricht,

The Netherlands.

More about this

In the computer installation, Mycelium, I was interested in blurring the boundaries between an artwork and the viewer (and by analogy the individual and society).

Behind a window-like opening, visitors could see an image (a composite of one of the art works by the other artists in the exhibition, with a close-up of one the people I live with). Instructions informed them that they could choose any image to interact with by typing words over the image. Two printed images then appeared from a slot. One image was a random image with their texts placed in another order over it. The other was the image they had interacted with. Each visitor chose one image to keep and the other was left to become part of a mushrooming installation.

The intention of the line of images and texts, the most visible part of this work, was not just to extend that moment of interaction into the surrounding public space but also to show a growing material manifestation of the exhibition itself; the art works and my personal interaction with them on the computer, and the visitors' interactions and presence in that time and space. Here the visitor could create their own 'mycelium' (organic system) and share their part of the story.

Making Salt made with Gaudi Hoedaya and Sarah Buist began

as a website and then evolved into a performance.

The website (http://www.

geocities.com/ SoHo/Square/1079) has a database of images that change

each time the viewer clicks on "filter".

They are images on the

theme of filtering information in our world.

For the performance at ISEA, in Manchester, people were ushered

in to sit next to each other in a central space towards the back,

while I sat in front of them typing text which was projected onto

five small screens in the front half of the lecture theatre.

There

was a large video projection on the front wall of various hands

filtering and playing with salt. The effect was that the changing

words seemed to move in the space in front of the changing images

and also to fuse into them.

While I was typing the 'filtered' texts,

which were to do with our senses, history, politics, the spirit

and science. Sarah & Gaudi poured salt into the palms of those seated

at the end of the rows and asked them to pass this on (and the salt

was filtered as it was passed on).

Ghandi

claimed India's right to define itself by extracting salt from the

ocean. This performance combined textural and visual references

to the process of filtering, where everyone was left with salt on

their hands.

What I have found hardest about living in the Netherlands

is that life seems so catagorized here. I use my children in my

art and in my art-making process not 'just' because I am a mother,

but because I am convinced that they are part of the real world

and my art is about the 'real' world!

Big Ones, consists of two larger than life-size translucent

photo-images of children who could be posing or playing. Their gestures

are ambiguous. One stands on one leg holding his head in his arms

and the other is bent over, feet wide apart, about to roll a rock

over the sand.

The title refers not just to size, but also to telling

'big ones' -stories.

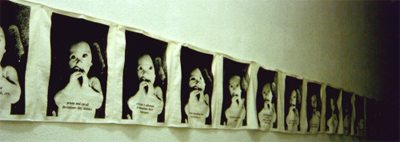

Wrapping for a marginal citizen is a 12 metre long cloth

with 24 identical images of my 6 month old son staring directly

at the camera. The various texts under-neath each image 'read' as

a sort of monologue-come-dialogue. They reflect comments made to

me when I had a baby with me on a train, in a gallery, or on the

street. It is also a piece about how I feel as a foreigner in The

Netherlands some days.

The video of the same name is quasi-biographical in that I use my

own art objects to tell stories, just as the children tell stories

in their playing.

Two voices: a cynical one and an optimistic one

'converse' as images of eggs being played with, being forced into

transparent egg-cups, being eaten and being broken merge between images

of my art objects being played with by the children.

The first and

last text for both the video and the cloth is: "It is a law of nature,

the strong survive".

In the piece Mutability (1993), I took a snapshot I made in

the Louvre of my husband and son and presented it in a form so that

the physical image 'mutates' in its visibility as the light source

changes. My starting point was resistence to the idea that motherhood,

or sainthood, was something set in stone.

In another work, Virtue of the Rose, I was examining the associations

between what we call an 'ideal' and what we call a 'characteristic',

and in particular I used the names of the Bahá'í months, such as '

Loftiness', 'Splendour', 'Questions', 'Words', etc, as starting points.

Our months, each nineteen days long, are also attributes for the divine. They are ideals and characteristics.

So I took these words, changed some, added some others and placed

them over the image of an open rose. The rose is a symbol of ideal

love and for me, a fitting symbol for the divine, because in the Bahá'í

writings, ‘love’ is repeatedly stated as the source of all things.

It is ‘love’ that attracts, and ‘love’ that inspires. Bahá'u'lláh

wrote that his first counsel for us is to "Possess a pure kindly and

radiant heart".

I engraved the text "Virtue of the rose" into the

deep frame to literally imbed it in the frame which symbollically gives

the image a context. The word, virtue, comes from the old English,

'virtu' which meant an inner strength or characteristic, while today

it means a 'good' quality.

I have often wondered how one could make an artwork which symbolised the soul. The sculpture, Parable of the rich fool, is an attempt

at this. The work consists of five polished transparent resin house

forms raised slightly above the ground and arranged in a semi-circle.

If you stand directly above each 'house' a text can be read refracted

through the roof. If you move, the text disappears and the house appears

both empty and full. It is a solid piece of resin but there is nothing

to see. The text is the biblical 'Parableof the rich fool' which tells

of a man who built houses to fill with all his possessions, but at

the end had nothing when God called for his soul.

Tulips

from Istanbul, is a piece about being here in the Netherlands.

The tulips appear to be of glass, in varying shades of orange,

and hang from the ceiling.

The aesthetic experience is a combination

of touching or playing and a few historical facts.

The tulip

was imported into the Netherlands and Germany from Turkey around

the year 1600, at roughly the same time as the House of Orange

became the Royal House of the newly formed nation of The Netherlands.

On the postcard relating to this work I have incorporated a

quotation from the Qur'án,

"It is not a tale invented,

but a

confirmation of what went before it..."

Surah Yúsuf 111

This chapter of the Qur'án refers to progressive revelation.

This is a concept that all religiousleaders or prophets come

from the same source and are part of the same eternal religion.

Here I connect this Moslem and Bahá'í view of religion to that

cultural symbol. The tulip was never a found object, it came

from somewhere, and in this instance, that somewhere was a Moslem

society.